Well, I think you know where the idea of dot really comes from. I appreciate Carl Sagan for his beautiful words.

Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us.

Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot, 1994

We do not stay the same

A few years ago, I started chatting with a friend on Facebook. After almost 4 months of online chit chat, we finally saw each other in real life. We kept talking and enjoying being with each other. But, at a point, that friend suddenly asked me why I was not as talkative and open as I had been before. “Does he think that I pretended to be friendly (and cute)?” – I thought. Actually, it wasn’t the first time I had that trouble.

I am an introvert – a kind of person that is not many people’s cup of tea. I imagine that there’s a secret club of introverted people. Why secret? Because introverted people don’t come close to each other and say out loud: “Hey, I’m an introvert”. We secretly recognise each other, or not – because many introverted members of the club are experts of hiding their introverted nature inside. That’s where the trouble comes from.

Again – I am an introvert. FYI, that doesn’t mean I lack the capability to communicate with others. However, it’s not easy for me to start a conversation in person. The online world is my ally that makes me invisible, yet lively and “visible” at the same time. In Vietnamese, we have a phrase to talk about someone who rarely speaks up in public but is extremely active in front of the screen, even giving aggressive comments on social media. “Keyboard hero” has a negative meaning, but it also points out how the online world becomes a safe place for many people to express another part of themselves. In my case, luckily, that another part is not a truly “keyboard hero” but simply someone more confident whose conversations are full of emojis, stickers and WOW. That means my online self is still me, it’s just another part of the whole me. The friendly (and cute) girl on Facebook and the shy girl of 4 months later are the same.

I wanted to tell my friend that to know a person is like to peel an onion because it takes time and, sometimes, tears. That annoying round white vegetable is a fan of layered clothing – just like how each person would carry many layers of identity masks. The more masks you can take off, the more you understand that person. (And the more you peel an onion, the harder you cry.)

The media have changed, so have us

Do you remember this scene from The Matrix?

Neo was told that each pill would lead to a totally different life. Well, here’s the right version.

The same thing happens to you once you join the Internet. At that place, although you choose either the blue pill or the red pill, you have to learn how to fit your identity in the Internet framework. How can you stay the same when Twitter gives you only 280 characters (the limit used to be 140 characters, which is said to be more elegant) to render all your complicated and abstract thoughts into text? In case you have too much to let the world know, you need to be as active as President Donald Trump.

What if you are on Instagram? That platform gives you no more than 24 hours to publicly give a secret hint to your crush on the story. If your crush continuously skips your story for more than a day, you lose your chance.

In short, you have to make yourself fit in the space that you receive from social media. It’s frustrating, but come on, you don’t pay any money for them. Everything they take from you is just your data. What else can you expect?

IoC = Internet of Changes

Human beings express themselves in communication so the change of the mediums transforms our lives in many ways. We used to talk to each other directly until we invented letters. Telephones and televisions have enlarged the distance of communication. Since the Internet sneaked in our lives through computers and mobile phones, the ability of communication has become unlimited. The mediums have changed, so have we. I am living in London while my parents are in Vietnam. At 1 am in London, when I am still partying with my friends, my parents start a new day at 8 am in Vietnam. A flight back to my country takes me about 17 hours. Luckily, Facebook is keeping us from falling apart. Every weekend, I enter Messenger, click the phone icon to call my mother. It’s just that easy.

But, wait, does that mean the Internet is bringing us closer? Let’s look back at our life about 30 years ago. I was born in 1991, five years after the economic reform of Vietnam. I was a kid living in a poor country, and the television was one of the most valuable items in the house. Most family couldn’t afford more than one TV. In low-income residential areas, the family owning a TV was the place that their neighbours hung out to watch the news every evening.

People used to put their only television in the living room, and many families’ timetable followed the schedule of TV programmes. At 7 pm, my parents, my brother and I gathered together, having dinner and watching TV. Two hours later, my parents fought over the remote because my mother hated all sport matches and my father didn’t want to cry for the miserable life of my mother’s favourite soap opera character.

My family used to follow that strict schedule until self cell phones came and changed our life. During the TV era in the family, each member knew the entertainment taste of the others: dad loved football, mum was into romantic movies, I wanted but wasn’t allowed to watch teenage TV shows because of some American romantic love scenes in there. But things started changing when mobile phones replaced the protagonist role of the television. Tiny little phones contain more than what any television has, and they divide my family into private pieces. Now what each person does on his/her own phone is none of the others’ business. My cell phone is my *“black box” that saves my personal life from people’s curious eyes. I don’t share my phone’s password, I definitely don’t share my messages. Just for sure, I don’t let my mother follow me on Instagram because my Instagram life should stay as a secret to her. Another side of me lives in my cell phone, which I keep close to me even when I am sleeping.

* About that “black box” idea, please search for the movie Perfect Strangers – the most remade movie in the history of cinema.

The Internet gives me several stages where I can perform the other parts of me. Facebook was the first social network I joined. The platform, from my point of view, is like hotpot – a pan of everything. On Facebook, you can “feeling amazing”, react to friends’ posts, comment to show off your sense of humour, sell clothes, buy goods and date. What else can’t you do there? Facebook’s information overload decreases the attention you get if you are not a famous account with the blue verification mark. That explains why I rarely talk to strangers in real life but I can comfortably sing to everybody on Facebook.

The medium is the message.

Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media, 1964

Televisions, computers, cell phones or the Internet are forms of medium, and the content is the way humans live in the symbiosis with those media. The life we used to know has been broken into fragments, forcing us to be tiny dots with secret identities in a huge, complicated network.

The market of identities

Where do people sell things? If you lived in a city, you would tend to go to supermarket to buy almost everything needed for daily life. Amazon is another option if you are too lazy to move yourself like most people nowadays. But if you want to sell YOU, where can you go?

People who have fame or gain fame thanks to the Internet vary from camgirls, influencers, mukbang eaters to traditional celebrities. These people manage the way they appear in public because they count on that to earn money. In 2014, Ellen DeGeneres twitted “If only Bradley’s arm was longer. Best photo ever. #oscars”. The tweet went public with a selfie photo of the post owner and some other movie stars such as Jennifer Lawrence, Brad Pitt, Julia Robert, Bradley Cooper. A photo of Ellen only would not go that viral, but the participation of the other stars made the world crazy. That star team was attending one of the most famous cinema events – the Oscar. They still spared a minute to take a selfie. You may wonder why it is important to mention that the photo was a selfie. This kind of photo doesn’t require either professional photography skills or high-cost phones. Therefore, selfies equalise people. If you own a phone with a camera, you can become a part of the game.

The selfie made the stars look more like common people, sold a more friendly (yet expensive) image of them to the audience. Do you think the idea of taking that selfie popped up in Ellen’s mind spontaneously? I don’t think so. Anything happened in the show was decided to happen. That wasn’t a naïve shot but was, in fact, an active action of identity creation, modification and selling.

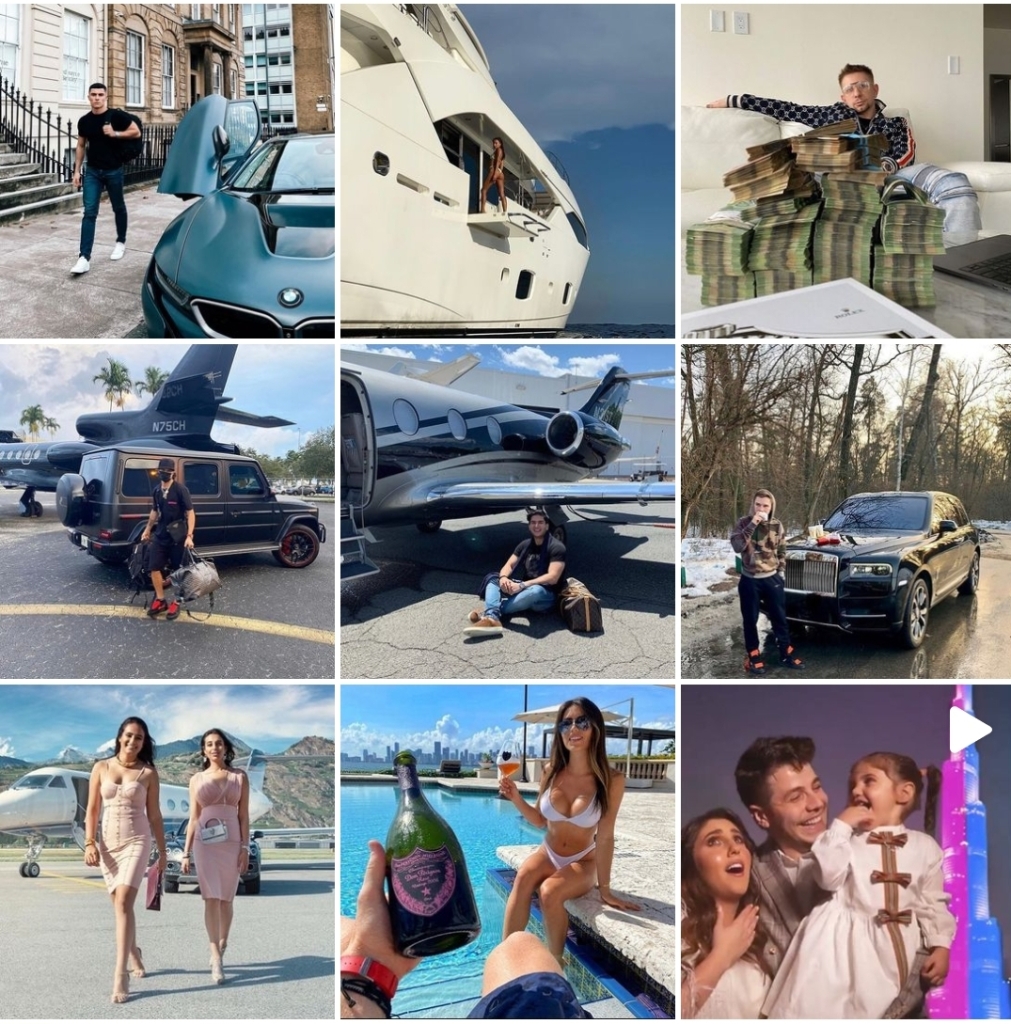

Who sells online identity to make money has to put effort into making that identity likeable. There is more than one way to achieve that goal. Instagram is a platform of photos; therefore, it is the perfect place for so-called rick kids to sell their luxurious lives. RKOI stands for “Rick Kids of Instagram” – a phenomenon of young adults who update their accounts with photos of expensive watches, bags, boots, cars or vacations.

Another way to be famous intentionally is creating a cultural distance between the identity producer and the audience. Mukbang videos wherein the eaters usually eat a load of food are quite common in Asia. However, they are still something strange and exciting for western watchers. Additionally, an internet celebrity can also attract viewers by being an expert in something. Each YouTube influencer tends to focus on one thing that he/she is good at – travelling, food or beauty products reviewing, makeup, technology, etc. Last but not least, don’t forget to keep your identity visible by updating about your life on a strict schedule.

All people using the Internet sell a part of themselves which might be personal information – such as name, age, gender – or diet recipes, #ootd, “a day in my life”. The Internet must be the strangest market, where people are willing to recreate and edit themselves, and then, offer the new identity to get benefit. When it comes to benefit, fame comes before money. That’s strange.